| |

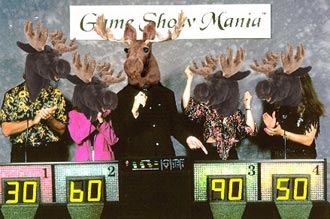

| { Punch Line } Robert Isenberg illustration by Dawn C. Bisi

Most of your readers already know who I am: Ted Smith, the guy with the moose head. You've already laughed aloud at my follies, and I don't hold it against you. But I want to set the record straight about my decision to move to Mongolia. That morning I packed the station wagon and headed for the state park, my girlfriend smiled widely and gave my hand a tight squeeze. When she giggled, I asked what was so funny, and she said, "You'll see." When I got home, I just sat on the couch and stared at my girlfriend, who sat in her wicker chair. The phone was ringing off the hook. I ignored it. The TV was switched off, thank God. I stared at her for nearly two hours. At the flight desk, I asked the rep where she would go if she wanted to be alone. She was primly dressed in a tight-fitting blue suit jacket, and she only blinked a few times. Sincerely, Ted Smith | |

Dear Boston Globe,

Dear Boston Globe,