Lost and Found: A Reevaluation of Brautigan and The Abortion

“Richard Brautigan is slowly joining Hesse, Golding, Salinger and Vonnegut as a literary magus to the literate young.”

— Look Magazine

In 1971, when Richard Brautigan’s fourth novel finally emerged, the country had two more years to wait for Roe v. Wade. Like the main characters in The Abortion, couples went to Mexico to make a choice that was still illegal in the United States. The Vietnam War dragged on; the New York Times began to publish the Pentagon Papers; opposition to the war continued to rage. Brautigan had gained a near-cult following with the publication of Trout Fishing in America in 1967, but it still took his agent over four years to find a publisher for The Abortion.

Some thirty years later, my friend Thomas lent me a copy of Rommel Drives on Deep into Egypt—he lent it indefinitely, as it turns out. I fell for Brautigan and quickly ran through all his books—both poetry and fiction—I could find. As many of them were out of print, however, I couldn’t find them without the help of eBay and a discretionary fund I lacked; though I now own a collection of Brautigan hardbacks and first editions, some of his early works continue to elude me.

I’d excitedly ask my college friends, “Have you read this guy Brautigan? He’s just amazing.” No, they’d say, never heard of him. Or: Yeah, I’ve read Brautigan—what a bunch of hippie bullshit. No one knew him, or liked him. When I did meet a fellow Brautigan lover, our instant connection resembled the cultish electricity between fellow fans of Buffy the Vampire Slayer: we were friends of the most meaningful sort, for life. I met a bearded boyfriend through mutual love of Brautigan and got my first job out of college because I charmed the owner of a graphics company with the Brautigan paperback I carried in my purse. I was proud of my esoteric literary taste, but a little worried at the extent of Brautigan’s disappearance.

At twenty, when I first fell for Brautigan, I was wistful, sensitive, and impulsive. My favorite word was “serendipity.” I wore my heart on the sleeve of my carefully aged hoodie and joined a group called The Love Revolution, which posted messages of goodwill on lampposts and in public restrooms. I wrote bad poetry. Was I a hippie? Not by a long shot, but I resembled the target audience of Brautigan’s flowerchild fictions. Things have changed, for better or worse, and while I still wear those old Converse All-Stars, I’ve caught myself calculating my moves, considering the health of my relationships, thinking about my so-called “career,” and examining my literary tastes with a more critical eye.

I love Richard Brautigan. I have loved him for many years now, and as I mature beyond the point at which my friends say I’ll “grow out” of my Brautigan phase, I only find new reasons to admire his writing. I begin to wonder, then, why I am one of the few who feel this way—why, as it turns out, Brautigan is not “magus to the literate young.”

What happened to the books, to the reputation, and to the memory of the man Richard Brautigan? How do we account for his disappearance from the so-called literary marketplace? If we remember Hesse, Salinger, and Vonnegut (and, within a limited audience, we do), why don’t we remember Brautigan?

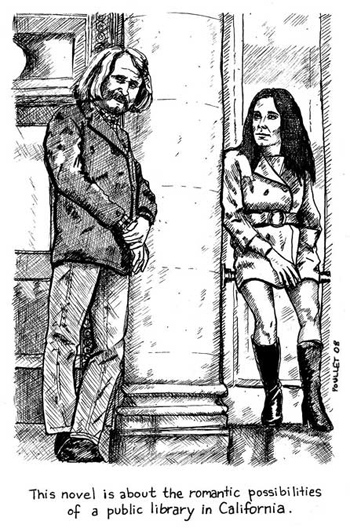

The Abortion is a fun book; critics and fans alike acknowledge the delights of Brautigan’s wit, the pleasures of his wordplay. The book’s main character runs a library housing the self-published books of the citizens of San Francisco, from an old woman who grows flowers in her hotel room to a child who writes about his love for his trike. This whimsical librarian meets a beautiful woman, Vida, and their romance leads to a pregnancy and subsequent abortion in Mexico. Only Brautigan would open his novel thus: “This is a beautiful library, timed perfectly, lush and American. The hour is midnight and the library is deep and carried like a dreaming child into the darkness of these pages.”

Some contemporary reviews of the novel cited Brautigan’s playful innocence as a flaw. Sally Sampson of the New Statesman wrote:

Amusing as they are, I must confess to finding Brautigan's parables a bit cloying; certainly a little of his faux-naïf style goes a long way, and it can degenerate into self-parody ("Vida had taught me to smell coffee. That was the way she made it"). However, his jokes are usually so good that one can enjoy the books for laughs without worrying too much about the message.

I take issue with this criticism; clearly under Brautigan’s wit a current of political and social critique runs deep and strong. Further, Brautigan’s work is always tinged with grief and loneliness, if we read closely enough; we don’t need his suicide or his letters to know that he was preoccupied with human isolation. A critic who calls Brautigan simply naïve is, in my opinion, not a very good reader.

Other reviewers took issue with how Brautigan’s style handled his heavy content. In those times, still years before the legalization of abortion, Brautigan seemed to manipulate his subject too deftly, to make abortion into a charming tale of personal growth when a more responsible writer may have overtly politicized abortion’s grim realities.

I wonder, however, how well such a book would do now, on the eve of presidential elections in the middle of a war often likened to Vietnam. Abortion is legal, but the threat of Roe v. Wade’s repeal is (debatably) stronger than ever. Our country’s youth is angry and disillusioned with a dishonest, inept leadership—or are we? Unlike our parents in the early 70’s, we aren’t as aware of politics or as involved in acting out our desire for change. I generalize egregiously, but I allege that our youth are complacent and the hippies of old have grown comfortable. I notice my own parents, who once lived in a converted barn outside Frankfort, Kentucky and worked, respectively, as a carpenter and for the Arts Council, now live in separate suburban spheres and happily shop at Best Buy. I love my parents, and I wouldn’t begrudge them their well-earned comforts, but that sense of middle-class satisfaction has bred in me an embarrassingly cozy disinterest in the vicissitudes of national politics.

If The Abortion were to be published today, the question might not be whether Brautigan handled his subject too lightly; the question would be whether abortion should be presented as a logical, acceptable choice at all. A rash of “unwanted pregnancy” movies have cropped up recently (“Knocked Up,” “Juno”) and, tellingly, abortion is never the choice taken, if even considered. I read magazines like US Weekly and InStyle, I admit it, and I’ve noticed an increasing emphasis on stars with families, pregnant celebrities, and celebutots paraded down the streets of L.A. in expensive strollers. When Jamie-Lynn Spears, 16, announced to the world that she was pregnant, it seemed only natural that she have the baby, and that the father marry her post-haste. Am I noticing a trend? Yes. Mass media in America is sending a strong, conservative message that the nuclear family again reigns supreme and that unwanted pregnancy should be handled by, well, making it wanted. Granted, the media do not necessarily direct public opinion, but they may reflect it.

What I am arguing is that I see our country becoming more socially conservative and less willing to acknowledge the possibility of abortion, though it is legal; we live in an economy that would reject even Brautigan’s “light” tale, a book-purchasing public that would fail to see (or instantly reject) both his scathing social critique and the value of his unsentimental portrait of an illegal abortion.

![]()

As writers our greatest anxiety is disappearance. Why else do we write but to communicate the indelible with a beauty and grace so unforgettable as to sustain our names into the violent, uncertain future? We want our books, if we ever write them, to be published and, moreover, to stay in print. But a book’s (or a writer’s) continued presence relies on much more than the brilliance of the writing itself; it depends upon an ever-changing popular mood, upon tastes determined by the political, social and economic state of a country fond of calling itself “free.”

I propose that Richard Brautigan has disappeared not because of weaknesses inherent in his writing—his books were glib, yes, but never inconsequential. I believe that Brautigan has disappeared because of our own weaknesses as readers: our increasingly reactionary political views, our interpretive laziness, and our unwillingness to believe that a playful, childlike style can hold in perfect tension both its own buoyant surface and its dark, hopeless secret. Brautigan worked to advance the form of contemporary fiction, but he also worked to tackle subject matter that could barely find a publisher. Would we publish Brautigan now, and if so, would an angry, active youth culture herald him as a hero? I doubt it. But will I fight relentlessly for Brautigan’s memory and for the reemergence of daring, controversial fiction? Yes, forever.

The return of legwarmers and reflective spandex is proof positive that our evolution is cyclical; with time and effort, we’ll see the return of Richard Brautigan.

Kelly Ramsey, when she is not eating cheese and forgetting to turn off the lights, co-edits the online literary magazine Hot Metal Bridge.