Newfound Splendor: An Interview with Ed Piskor

Half a block from the house I grew up in was a little neighborhood pharmacy, where in the back, across from the lottery machine and ice cream counter, a small wooden display shelf held rows and rows of glossy magazines. On the top shelf , well out of reach for any kid my age and height, were the nudie mags; in the center a slew of current events periodicals and trashy gossip rags. But the bottom shelf, right there at little kid eye level, housed an exploding fever dream of bright primary-colored fantasies of aliens, mutants, and super-powered heroes.

My grandmother bought me my first comic books there and for that, among many countless other reasons that flood my mind when I think of grandmother, I will be forever grateful.

For a little kid owning a comic book is transformative. For all of their simple exclamatory dialogue, comics had might as well been written in some unbreakable code. Parents didn’t get them, and all too often, to the point of becoming an urban myth, some poor kid’s mother tossed his comics in the garbage bin with the egg shells, used coffee grounds, and all the other obvious trash, never once considering that she might be destroying something of both cultural and monetary value. Kids, however, knew better.

To read and own comics meant you were a part of something both private and communal. Misunderstood, or simply shrugged off as nothing special, by adults tended to isolate a kid’s experience with comic books as something completely outside of the adult realm. This also meant that discussion and dissection of comic books was wholly the province of children. I recall many backyard conversations about the fate of a particular character or the latest storyline in a favorite title and many readings and re-readings of the editor’s responses in letter columns trying to glean some small tidbit of info regarding what was coming down the line in a book. (Sidebar – my very first experience of publication was having a letter I wrote printed in an issue of Uncanny X-Men.) I couldn’t imagine an adult taking part in this sort of behavior, and to be honest, I didn’t want adults invading the world of comic books.

Well, that was then. Now I am one of those so-called adults and my love for comic books has not waned in the least. If anything I’ve become an even bigger (true-) believer in the form.

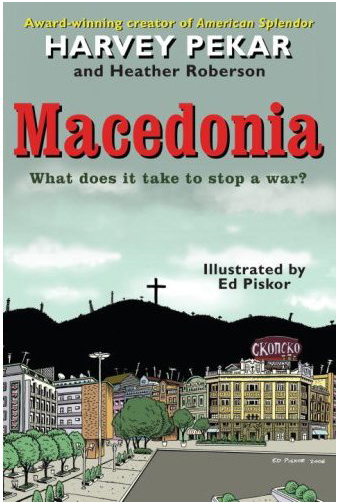

Comics writer/artist Ed Piskor still remembers, what in retrospect was the last hurrah for a certain kind of experience for a little kid to have with comics. Ed’s star is on the rise in the field. Harvey Pekar’s Macedonia, a full-length graphic novel for which Ed did all of the artwork, was published in June of 2007. Another collaboration with Pekar concerning Jack Kerouac and the Beat Generation has just been completed and will be published in the very near future. Also, Ed has just self-published the first volume of Wizzywig, an ongoing project concerning the early days of computer hacking.

Recently, I had the opportunity to talk awhile with Ed about our mutual love of comic books.

Ed, tell me about your earliest memories involving comics. Where and when did you first encounter comic books?

My parents spoiled me rotten. I grew up owning a ton of cool toys and I don't remember a time before owning comics. I've always had them and just accumulated more and more of them as I got older. I didn't care much about the production aspect of them but they provided a really cool visual experience that I got a lot out of even before I was able to read the words. I was able to tell what was going on when I was looking at the well done comics and that was enough.

What initially attracted you to comic books? What did you read as a kid? Why those titles in particular? Did you ever fall into the Marvel versus DC camps? Were you aware of comics as a collaborative art form - writers, pencillers, inkers, colorists, letterers, etc.? When did that realization come to you and did it affect how you thought about comics, or how you read them? For example did you have fave writers, pencils, inks?

I consider myself to be a part of the last generation of kids who were reading comics from newsstands. I

was able to grab them from the drug store or the super market or any number of places. Comics were easily attainable in the 80's. I feel bad for kids now because they really have to do a lot of work to get their hands on a comic.

I didn't fall under a particular companies bandwagon. I was happy to get my hands on any and all comics possible. I was very indiscriminate. The only thing I hated about comics was picking something up in the middle of a story arc because there was no guarantee that I would find the next issue on the shelves the following month. The stores displayed a sporadic selection of comics and might either sell out really quick or just skip an issue here and there.

The credits box in comics, that housed the names of the creators, sealed my fate as a cartoonist. As a kid reading these things and seeing that they were actually produced by human hands meant that I could do their job if I worked really hard at it. I decided that I was going to make this my life's work at very

early point and that's all I ever wanted to do and still, even when I'm dragged from the drawing table, that's still where I'm happiest and most comfortable. It's a deep habit that, like the most terrible habits, causes me to be very withdrawn from most everybody around me.

One of my favorite collaborative teams as a kid was Chris Claremont and John Byrne on X-Men. I was too young for their initial run but I real Classic X-Men which reprinted their run and I was always so blown away by those comics. I had a huge crush on Kitty Pride too, I'm shamed to admit.

Were you aware of the stigma attached to comics - bad art, bad writing, entertainment for illiterates,

low culture trash? If so, what effect if any did this have on your enjoyment of the books? Guilty pleasures? Or a kind of punk rock defiance?

I wasn't aware of these stigma's until very late. I'm talking recently. I mythologized it so much most of my

life and to see that it has no meaning to almost anybody is really kind of heartbreaking. I'm so proud to be a part of this field but it is such hard work and so competitive that the added headache of not being understood by loved ones and friends really can take a toll on you. Try explaining to people that you HAVE to do something but you might not get paid for it, it might not even be published by anybody

other than yourself, but you still have to do it anyway because there may be a real payoff in the end or that it is just necessary to keep sane. I have so much fun doing the work but, man, I feel extreme guilt on a constant basis because of the people around me. I'm very lucky to have some tight cartoonist friends that are going through the same constant bullshit. Comics really is respected only 1 step above graffiti. I'm sure that if I attain a high level of success everybody will eat their words, too, which is a goal that keeps me in the “eye of the tiger” mindset.

Had you always wanted to make your own comics? When did you first start? What were those early

efforts like ie. when Crumb began he had an affinity for Disney-type funny animal adventure stories. Did you model your work on anyone in particular. Were there certain stylistics that attracted/repelled you even in this early stage?

I always wanted to do comics but I thought that maybe I would just end up drawing X-Force or something like that. I didn't really know that people did their own comics until way later. I have to confess that the first comics I put together were very much in a Rob Liefeld, Todd McFarlane style. I was in 3rd grade so give me a break. Ha ha.

Was your interest in comics a solitary interest or did you have a group of friends also into comics?

How did this affect your reading/understanding of comics?

There were 2 periods of time in my childhood where a lot of kids were reading comics. When I was in around the 3rd grade or so they seemed to be everywhere, so I didn't get hassled for wearing Spiderman shirts when other kids were wearing zubaz gear and cross colours. Also, when Image came out I was in middle school and even jocks had comics then. Everyone’s interest quickly disappeared when they realized that their copies of Spawn #1 weren't worth $40 anymore.

When did you become aware of adult/underground comics? What books/artists grabbed your attention? What was your initial response to these kinds of comics? Was your mind blown? Where did you first encounter them ie. through a friend, catching sight of them at a shop?

I was in about 5th or 6th when I was scanning through some channels on tv and saw the documentary Comic Book Confidential on cable. I was so amazed by this film because it didn't highlight anything that I ever heard of. I considered myself well read in comics but I instantly became aware of a much wider range of material that I needed to get my hands on. It also showed me that there were whole stores devoted to comics which boggled my mind. I needed to check out all of that stuff. It all seemed so naughty and subversive and I couldn't help but be attracted to that stuff.

The first time I read Crumb or any of those underground comics was when I went to the library shortly

after seeing the movie and looking for books on comics. I found a book called Comix by Les Daniels that contained so much gnarley stuff that I couldn't believe what I was seeing. The book includes work by

Crumb, Jay Lynch, Kim Deitch and a bunch of other people who I consider to be heroes of mine. What's funny now is that my work is appearing amongst these guys in the pages of Mineshaft magazine on a

regular basis and I can't tell you how excited this makes me feel.

Were you a fan of Harvey Pekar's work prior to working with him? When did you first encounter his work? What was it about Pekar's comics that you admired? Was there anything that you found off-putting?

I was really into Pekar's work prior to collaborating with him. I might have been one of his youngest readers back when I was still in the single digits of age. Don't get me wrong though, initially I was extremely confused about what American Splendor was. I thought that the title was like Pekar's superhero name or something. I kept waiting for a big conflict and was excited to see what Harv's super powers were. It didn't take long to realize that wouldn't happen in this comic book so I just kept checking it out to at least see if there was a punchline to the stories which there really wasn't. It took some time to figure out what was going on but as I got hip to the fact that these are "no b.s" slice-of-life stories, but when I was clued into the joke I couldn't put his stuff down. Though some of that artwork made me want to stab my eyes out.

You first worked with Harvey on a comic in the Our Movie Year trade. How did you get that gig? Had you been in contact with Harvey prior to working with him or had he contacted you?

I was working at a crappy call center paying off some school loans while I was putting together some small strips here and there. I wasn't very sure on how to get a wedge into the comics industry so I just sent copies of my strips to every company and cartoonist whose address I could find. I got Harv's name off of the front cover of one of his comic books and I wasn't sure that he would have his real address on the front but I sent stuff anyway and it didn't get sent back so I just kept sending anything I did as I finished it. It was a pretty awesome phone call to get because the movie was freshly in theaters and in peoples minds. I imagine he must have received a bunch of submissions in those months. He simply offered to toss a script or 2 my way. It took about a year for that to come to fruition and then he almost immediately offered another script. After that he asked if I wanted to draw a whole book.

Harvey is kind of a unique animal in the undergrounds, being primarily a writer he has worked with hundreds of different artists each with his/her own vision of how to present Pekar's world. What is Harvey's mode of working with artists? Often he includes stick figure drawings with his scripts as an aid to artists. Was this the case with you and did you adhere strictly to Harvey's 'stage directions' or were you given a fair amount of latitude in your artistic choices?

Harvey is extremely low maintenance when it comes to producing his scripts as comics. He doesn't ask for many changes if ever and for precisely this reason I think that is why a lot of his artists’ work is a bit substandard. They know he won't ask them to change it. Harvey’s scripts are these pieces of typing paper that are sectioned off into panels with little stick figure drawings talking back and forth. Maybe a little character direction and maybe some idea for the context and background of the story. When I drew my first script for him he required me to send him my penciled art to make sure that I could tell a story in pictures and to make sure I didn't draw him with a ray gun or superhero tights. After the first few scripts he was confident enough to let me do pretty much what I wanted to with his scripts which was very important on the Macedonia book because I needed to come up with a way to cram a 300 page script into 150 pages.

When did Harvey approach you with 'Macedonia'? What was your reaction to the project? Was this the largest undertaking thus far in your career? What were your concerns/worries going into the project? What excited you the most about it?

Shortly after the American Splendor: Our Movie Year work that I did Harvey asked me if I would be interested in doing the Macedonia graphic novel. I was a bit freaked out because I had no idea what to expect. At first I thought it was going to be a period piece about Alexander the Great or something like that but it turned out to be a more current story that just so happened to require the same amount of painstaking research on my part. I've never been far from Pittsburgh so I had no clue what the province of Macedonia was all about. I didn't know what the architecture was like. I didn't know even what side of the road these people drive on, etc. So there was a whole lot of behind the scenes work that was required to give the book some sort of authentic feel. Unfortunately, when I do the research I tend to feel like a slacker because I am not putting pen to paper and creating a comic page but hours and hours and hours of research were needed. That wasn't much fun. The most exciting aspect of the process was simply the idea that I was putting a whole book together. I was working towards the goal of seeing something that contained my name on it and that was my driving force.

Macedonia is somewhat different from Pekar's typical American Splendor work in that he is telling someone else's story. Do you feel that Harvey's voice is absent from the work? Or do you feel that Harvey's adaptation of Heather's work (Heather Roberson’s experiences in Macedonia and her research on the subject are the source material for the graphic novel.) allowed Harvey's own voice to peek through?

Heather was a major force behind the book. Harvey asked her to compile notes on her trip to Macedonia and she came back with a fully realized story. Harv took her script, added some stuff and took some stuff away but it is mostly her tale.

Macedonia is a large piece of work. What was your work schedule like while doing the book? Were you able to maintain a life outside of the work or was it necessary to put everything else on hold and completely immerse yourself in the work? How did that affect you personally and as an artist?

All that I want to do is draw comics, man. My work on Macedonia spanned 14 months of solid drawing everyday. 7 Days a week. 8 hours was a short work day for me and I counted almost 30 all-nighters while working on the book and I didn't mind one bit. I'm most happy when drawing comics and when people drag me away from the drawing board too long I begin to get extremely irritated and start feeling crazy. It became necessary to cut a bunch of people from my life who I deemed counter-productive to my goals or who were trying to keep me from what I needed to do. I have no problem sacrificing anything so long as I can do comics. My real pals understood and put up with me saying "no" all the time but a bunch of people wanted me to wade in the shallow pool of mediocrity with them and I had to tell them to "beat it".

The cool thing is that I have some great friends who are cartoonists and they go through the same bullshit with their friends and significant others as I do so it is very therapeutic to have a few people to commiserate with. I don't even expect anybody but another cartoonist to imagine what I'm about because it certainly isn't normal behavior to draw all day, to do a job on a freelance basis and have to continue looking for work constantly, etc. For the most part everything is pretty intangible until the actual work is printed and then you can show the normal person like "look, this is why I spent all that time in the basement" and they kind of get it. It is a weird business to want to be a part of so I only expect civilian friends and family to put up with me rather than understand what I'm doing. The "cartoonist boot camp" of Macedonia was a very fun and welcomed exercise. I will do this kind of thing until I die.

I don't think I've read any reviews of Macedonia that somewhere in the mix didn't mention Joe Sacco. I understand that you had not read Sacco's work, and in fact made a point of not looking at it while working on Macedonia. Is that true? Why did you feel that was necessary? Have you since looked into Sacco's work? What do you think of it? Is it fair that Macedonia, at least in the eyes of the critics, exists in the shadow of Sacco's work?

I confess to never reading Sacco's comics. I hear that they are pretty awesome and they are on my list of things to read. I certainly stayed away from his work when Harv asked me to do the Macedonia book. I didn't want to absorb any of the ways he did things. Macedonia can in no way live up to what Sacco did for a million reasons, the main one being that he lived through the stories and told them first-hand. We're telling a filtered version of Heather's story through our own prism so it's impossible to be as intimate with the material as Sacco is. I always say that if people are gonna read Macedonia expecting to read something in the style of Joe Sacco it's going to fall right on it's face.

Macedonia is particularly wordy for a comic. Do you think this has limited the possible readership? What has the response been to the work? Do you believe the project was successful? My own experience of reading the book was that it felt too much like what it was: an adaptation of an academic thesis. Most of the scenes consist of Heather either talking to some political representative or else monologuing into a tape recorder. Were you concerned about this when getting the script? The telling of the story isn't especially dynamic, as the artist did you find this frustrating or challenging?

Extremely challenging and frustrating in the same breath. The reviews were certainly mixed and all of the negatives that I saw had to do with what you explained. I get emails regularly from people who read the book and were into it but I am the first one to admit that we were asking a lot from our readers on this project. There's a lot of information to absorb in this piece. Harv and I just completed a strip for the DC/Vertigo American Splendor mini series where we give one particular critic both barrels because they didn't explain their argument well at all. We gave it to him good.

You're currently working on a new project with Harvey about the Beat Generation. Can you tell me a little about that?

So I did about 120 pages of comics with Harv for a 200 page book. The book is going to be filled out with Essays and some other comics as well. We did 3 stories based on Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Burroughs individually and then we did about 10 other little strips highlighting some more important, but peripheral, characters of the movement.

We talked a little before about the stigma attached to comics, at least there was when we were younger. The market for comics, as individual monthly issues, may be shrinking but the market for trade compilations and graphic novels is expanding. How do you feel about that shift? How do you account for it? How did comics become respectable?

The question of the respectability level of comics is something that would take pages to really get into. Ultimately I think time will tell if these books are truly being taken seriously. I think it is really cool to get some mainstream attention for comics. That certainly can't hurt. I am afraid that a lot of people are producing comics only as presentation pieces for pitch meetings in Hollywood studios or trying to broker some sort of option deal. Like most businesses, when something catches on, the market gets flooded and it overwhelms the consumer plus quality control goes way down. It seems to be a natural cycle for comics. As a cartoonist, I kind of fantasize about the days of producing a regular monthly or semi-monthly book to have a bit more of regular payoff. It's really tough to disappear for a year and work on drawing a phone book’s worth of material.

The demographic for comic book readership has shifted. I don't know if your experience is the same as mine, but when I started seriously collecting in the mid-80s there were a lot of pre-teen and teenage kids (almost exclusively male) and some twenty-somethings in the shops (which there were also more of). Now when I visit the shops the youngest patrons are typically in their 30s (my age) and older with some twenty-somethings. What happened to all of the younger readers? Even at cons these days I seldom see kids unless they're being dragged around by their parents. Have comics lost the ability to reach younger readers? Or has the industry abandoned this demographic?

Comics became a victim of the direct market. Focusing on distributing to comic shops that aren't necessarily located anywhere near where a kid may stumble upon them proved to be a big mistake. I'm convinced that if a kid stepped into a well laid out comic shop they would go into sensory overload and become very interested in cracking open a book but they might not know these joints are out there. If comics would have continued being distributed to department stores, drug stores, and grocery stores, kids would be aware of them. I think that the publishers are pretty aware that in order to survive they need to appeal to these kids who will one day have discretionary income. What's funny is that I have probably 5 cousins who are children that have Wolverine or Spiderman toys but they have never seen a comic.

A few months back the art critic for The New Yorker, Peter Schjeldahl, made an interesting statement. He said that Comics today are what Poetry was in the 1960s suggesting that Comics have gained a certain hip cache among the cool cognoscenti and intellectual outsiders. Do you agree? What does this say about the position comics hold in contemporary culture?

I'm not sure if comics are hip right now. I know that some hipster douchebags have gotten into comics because of their niche appeal and stuff like that. In my opinion, this "hipness" thing is just going to be a replacement of the "grim and gritty" phase of the 80's-90's. There are going to be a load of unreadable and indecipherable hieroglyphic-type comics on the shelves and by virtue of being obtuse and hard to understand, these "intellectual" people will start thinking about and finding meaning in this garbage. Since I deal with enough of these silly readers I found that the word "fascinating", when blurted by these comic scene-sters, means "I have no fucking idea what the hell I'm looking at but I'm going to try damned hard to make a poignant statement as soon I think of something".

Comics are being taught at universities, getting reviewed in the New York Times, being carried by book shops and not just specialty stores, R. Crumb was one of the featured artists at the last Carnegie International, etc. etc. Has the underground gone mainstream? In the book Eisner/Miller, Frank Miller argues that the new respectability accorded Comics is disastrous. He suggests that by being accepted by the Academy, Comics has essentially signed its own death warrant. Miller maintains that Comics must retain some of the old stigma to remain a dangerous art form, to continue to have meaning. How do you respond to that?

Frank has always been a real romantic when it comes to talking about comics. I don't think that this will be a death warrant for comics by any means because people, even for no money, people will still be interested in telling stories this way. Certainly the creme will rise and the best people will have some incentive to keep producing and maybe there won't be enough opportunities for people who probably deserve the chance and they may quit but I don't see comics going away anytime soon. Everyone I know will keep doing them.

Frank has always been a real romantic when it comes to talking about comics. I don't think that this will be a death warrant for comics by any means because people, even for no money, people will still be interested in telling stories this way. Certainly the creme will rise and the best people will have some incentive to keep producing and maybe there won't be enough opportunities for people who probably deserve the chance and they may quit but I don't see comics going away anytime soon. Everyone I know will keep doing them.

Regarding your question about the underground going mainstream I think American Splendor is the best example. Harvey used to publish and distribute those books himself, and now the comics are printed by the same publisher who brought you the Da Vinci Code. Now there certainly is work that falls way under the radar of the mainstream but there is a way bigger awareness of comics as being more than just cape-and-cowl than ever before.

As we sign off, let me throw some names at you and respond with your immediate reaction:

Robert Crumb

A drawing machine! I have his life’s work in some form or another and I love watching him

grow as an artist. It makes getting better feel more tangible.

Jack Kirby

The king. I can't believe this guy’s excitement, imagination, output or way of thinking.

He really knocks my socks off. I really am going to start copying off of Kirby a lot more. You heard it here first.

Los Bros. Hernandez

I know I will be accused of being low brow and shallow but I really like Jaime far more than Gilbert simply based on how beautiful he draws. He's as close to perfect in execution as I've ever seen.

Jack Cole

I read a bunch of his stuff over the years. 1, the material is so much fun. 2, he is a

master of dynamics and designing a page.

Charles Schulz

I've been studying his work a lot more nowadays. Peanuts really is the best comic strip there will ever be and everything else falls far behind.

Will Eisner

I read his work and consider those Spirit stories to be the perfect textbook on learning how to do comics that you will ever find.

Frank Miller

This guy’s comics were really fun to me as a kid. He was a god to me when I started having testosterone pumped through my scrotum during puberty but now my fanboyishness for Frankie has calmed down a bit.

Kim Deitch

Kim reminds me that there is always someone working harder than me in comics. His work is so painstakingly beautiful. He is also very encouraging to me personally.

Steve Ditko

Ditko rules. His Spiderman comics are the only Spiderman comics. Also, his work in Creepy and Eerie is beautifully crafted.

Herge

I haven't read much TinTin but I really like the way his stuff looks. I appreciate his intense use of reference and his ability to break down the reference into very “simple” forms.

Winsor Mckay

I love that Mckay was so brilliant and such a craftsman but he didn't think to do his lettering before he drew the balloons so he had to squeeze in the dialogue. I have seen a bunch of his original material and it blows

me away.

Harvey Pekar

I am extremely thankful to Pekar for wanting to work with me and I'm a huge fan of his writing.

Who would you add to this list?

I can go into detail with the EC comics guys and a zillion alternative cartoonists. It's best that you capped the names this far because I can go on and never stop.

![]()

Ed Piskor is a hardworking illustrator based out of Pittsburgh Pa. He's happy he gained some traction developing a cartooning career quickly after his tenure at The Joe Kubert School of Cartoon and Graphic art. His best known work right now is his collaborations with Harvey Pekar on American Splendor. He and Mr. Pekar are currently wrapping up a graphic novel called MACEDONIA for Random House.

Kristofer Collins is managing editor of The New Yinzer and owner of Desolation Row CDs. A book of his poems entitled King Everything was published in 2007 by Six Gallery Press and is available in local shops and at Amazon.com.The Liturgy of Streets, a collection of new poems, will be published later this year.