| |

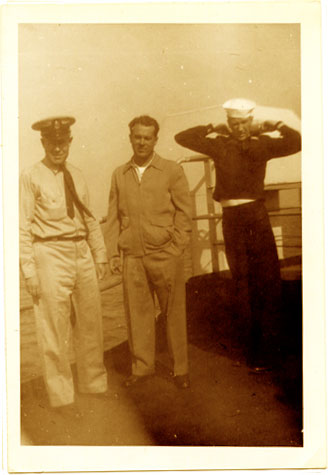

| { By the Time We Get to Al Nasiriya } Steve May photography courtesy the Patterson family

Joe, 57, born in Pittsburgh during the Battle of the Bulge in 1944, did not fight in the Vietnam War, but his best friend Jim did. Jim was born a few months before Joe on April 4, 1944. The two attended St. Joseph's elementary school and secondary school, and, eventually, Duquesne University. They graduated in the late spring of 1968, just after the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong launched their Tet Offensive, not long after Eddie Adams' famous photograph of South Vietnamese General Nguyen Ngoc Loan executing a Viet Cong prisoner with a single silent bullet in the head in Saigon, now Ho Chi Minh City, appeared on the covers of newspapers around the globe. Joe became a teacher; Jim was drafted. For someone born after Vietnam, war thus-far has looked and felt clinical and easy, approximately like this: We successfully invaded Grenada (nineteen Americans dead) and Panama (forty Americans dead) in about one day, combined; we defeated Iraq in the Gulf War in less than a week of fighting on the ground (363 Americans dead for the whole conflict), with most of the free world represented alongside us in one way or another. We watched all those on television, and the Gulf War in particular, with all its black-and-white video-game images of smart-bomb strikes on various Iraqi buildings, made for good, compelling TV. We were not shown the part about the innocent civilians dying of typhoid and cholera as a result of our bombing of usable water supplies. The problem, as Jack, who is my grandfather, sees it, is that the world is not together on this one. The United States failed spectacularly in its attempt to build consensus in favor of a war on Iraq, and is now left to go at it more or less alone with the UK. Victory, though Jack notes that it could come at greater American loss of life than anyone in this day and age is prepared to stomach, is a foregone conclusion, and was before a single Tomahawk Cruise Missile was fired. What will happen next, after we topple Hussein and disarm Iraq? A rogue state may (it is true) occasionally sponsor a terrorist group. That is simple opportunism: even civilized states such as the US have done it. But states and terrorists are not natural allies. Terrorism is what some people resort to when unable to exercise their will through government. If ... Baghdad does prove the last capital in the world which dares raise a fist to Pax Americana, then what is the logical conclusion for (for instance) Islamists to draw? To quit al-Qaeda?In the Chinese jungle, on the evening of VJ Day, Jack and his comrades put down their guns. One needless death was enough. In Iraq, with American forces—many of which have bypassed bloody Al Nasiriya altogether—sixty miles south of Baghdad, it is too late for that now, and all but the most radical and/or naive among us must now face that fact: We have no choice. This war, though we did not ask for it, or want it, though there was nothing we could do to stop it, is now ours. But we do not have to be silent. In his Sunday Times essay, Matthew Parris pointed out correctly: "George W. Bush is not America; he is the current U.S. president. It is not the same." Do not forget: Less than one year remains before the start 2004 presidential campaign. Let us dissenters sharpen our political knives and unite. The author wishes to acknowledge the following sources: Jack Walker Russell, Walter Joseph May, the New York Times, the American War Library, and the Sunday Times (London). May James Poulusney rest in peace. | |

Peace. Peace had finally come to the world with the Japanese surrender, and now it was night. Jack, age twenty-three, was celebrating with his Army Air Corps comrades in the Chinese jungle, drinking and playing cards. The war was over and godammit, they had won. One of the pilots, whose mission the next day would be to fly a load of money to another spot in China, decided to check his C-47 twin-engine transport to see if the weight was balanced. He left the thatched-roof hut and walked into the night. Not long after, a gunshot rang out. A Chinese guard had mistaken him for a looter and shot him. The pilots and crewman went for their guns.

Peace. Peace had finally come to the world with the Japanese surrender, and now it was night. Jack, age twenty-three, was celebrating with his Army Air Corps comrades in the Chinese jungle, drinking and playing cards. The war was over and godammit, they had won. One of the pilots, whose mission the next day would be to fly a load of money to another spot in China, decided to check his C-47 twin-engine transport to see if the weight was balanced. He left the thatched-roof hut and walked into the night. Not long after, a gunshot rang out. A Chinese guard had mistaken him for a looter and shot him. The pilots and crewman went for their guns.