| |

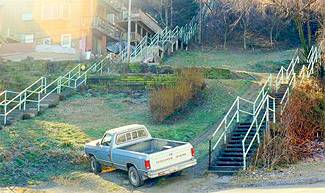

| { Staircases of the South Side Slopes } Robert Isenberg The stairways that snake along the South Side Slopes are like labyrinthine installation art, with no famous artisans to take credit, no names to give them distinction. What marks these staircases are weathered imperfections and rubble: spotted with moss and shaky with age, they've been refined by thousands of pedestrians for scores of years. | |

The most glorious specimens crawl along the cliffs, twisting around and around, reminiscent of the impossible architecture in traditional Chinese watercolors. Several excellent staircases extend from Arlington Street, which is embedded with a large section of T tracks. One set turns an abrupt corner, angling downward, and ends in a pit that was once a building's foundation. It may be cut short, but like all ruins, it connects us to an earlier day, when that shattered wall was somebody's front stoop.

The most glorious specimens crawl along the cliffs, twisting around and around, reminiscent of the impossible architecture in traditional Chinese watercolors. Several excellent staircases extend from Arlington Street, which is embedded with a large section of T tracks. One set turns an abrupt corner, angling downward, and ends in a pit that was once a building's foundation. It may be cut short, but like all ruins, it connects us to an earlier day, when that shattered wall was somebody's front stoop.