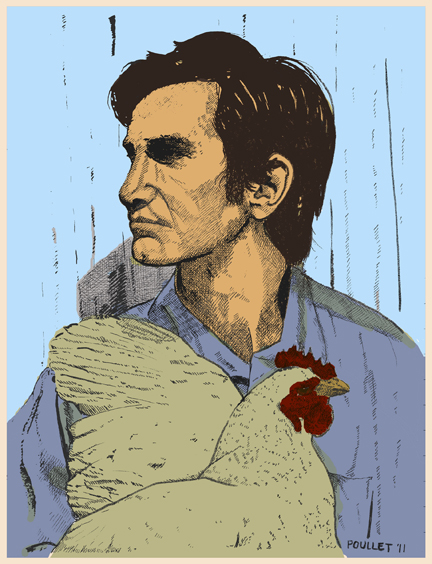

The Worse the Voice, the Better the Song: On Townes Van Zandt and Radio Disney

Dave Newman

Townes Van Zandt wrote brilliant lyrics. He played guitar like a banjo. He had almost no voice. I mean all three of these things as compliments, but especially the last one—truly, Townes Van Zandt couldn’t sing a fucking lick. It’s why so many of his songs still sound great: Townes couldn’t lie. Lying is what you get on the radio. If it’s pitch-perfect or, more likely, pitch-corrected, it’s not true. Townes Van Zandt was true.

Years ago, when I was maybe twenty-one and buying up every Townes album I could find, I cornered my brother late at night in my car after the bartender at the Pipe Room, a local dive bar, kicked us out at closing time. We were both pretty drunk. My brother wanted to get more beers. Or a pizza. Or even a donut from Sheetz. I wanted to listen to Townes. I wanted my brother to listen to Townes. We bickered like that until we made it back to my brother’s place and parked the car. He said, “Fine,” just to shut me up, and he gave it a listen, one whole song. He closed his eyes. He leaned close to the speaker. I believed he was being moved. I believed he was being changed. He opened his eyes and looked thoughtful. He said, “Yeah.” He said, “It may be romantic to drink and smoke yourself to death, but I don’t want to listen to it.”

It was a great insult, a hilarious insult, but I still hear it as a compliment.

You listen to Townes Van Zandt one time, one song, and you know he’s serious.

Townes Van Zandt was not here for the punch bowl.

Some of Townes’ best songs focus on the downtrodden—not just the unemployed but the unemployable, not just the user but the addict, people who demand the world leave them nothing because nothing is all they want.

Take the song “Marie” from Townes’ last studio album. The narrator of the song is a guy living in a mission. He’s looking for work. He can’t find any. He meets Marie and falls in love, but women aren’t welcome at the mission. It’s summer so they decide to live outside, under a bridge, homeless. Even a job moving old cars is beyond this guy’s reach. His unemployment checks run out. Winter’s coming. Marie needs a coat. She gets pregnant instead. I’ll stop there, but more bad things happen. The worst things happen. It’s a hopeless song, as all songs about poor people who stay poor are, but it’s filled with love too. Even in death, there’s remembrance and the chance to meet on the other side.

My favorite version of “Marie” is on Last Rights, a hodgepodge of interviews and live recordings. I said before that Townes couldn’t sing. By the time he recorded this version of “Marie,” his voice was completely shot. Years of booze. Years of travel. Years of drugs. But people like Marie can’t sing either, and neither can her boyfriend. The world doesn’t want them to find their voices, so they don’t. Townes found his voice.

His voice is best when he whispers, when everyone else would have shouted it out.

I listen to a lot of Radio Disney. I have a six-year-old daughter who loves Justin Bieber. We drive around and girl-scream and giggle and hope they play “Baby,” so we can giggle and girl-scream even louder.

It’s a lot of fun.

The music they play on Radio Disney is as bad as you think.

It’s music made for money, nothing else.

Lots of songs sound the same. Some songs even use the same sample. The big stars sing on the other big stars’ songs. The drums are drum machines. The guitars are keyboards. Most of the voices sound like computers. The guest rappers sound like computers.

If you’re six and have a poster of an asexual Canadian teenybopper on your wall, this is fine, it’s great, it’s fun, you’ll outgrow it.

But when I listen to mainstream radio, even alternative radio, even Public Radio, especially Public Radio, I’m shocked that it sounds exactly like Radio Disney. Bands that can play try to sound like they can’t. All the individuality has been produced out.

My wife really likes Jesse Malin. Jesse Malin is a punk rock/glam rock guy who became a singer-songwriter when his other bands broke up. My wife loves his first album, The Fine Art of Self Destruction. It’s a good record. I like it, too. There are lots of acoustic guitars and pianos and thoughtful lyrics about New York and growing up and falling in and out of love.

Not too long ago, Jesse Malin released a new album. It was called Glitter in the Gutter, a very bad title that, I’m assuming, is an allusion to Oscar Wilde’s famous quote, “We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.”

I gave Glitter in the Gutter a listen. Because I paid for it, I listened to it again, then a third time. It wasn’t music, even if it was technically music. It was a commercial for music. The album was so produced I could barely hear the songs. There were some good lyrics in places, but I had to listen for them. The rest sounded like a video game, one you don’t want your kid to play.

Bands used to go into the studio to capture what they sounded like live. They wanted imperfection. They wanted realism over fantasy. It worked. Instead of gloss, instead of kiddie-pop, you got a voice with a rip in it and the wrong note that became the perfect note after a couple plays. You don’t listen to old music—any old music—and think: what that needs is more Casio keyboard and a drum machine and 19 back-up singers, all of them prepubescent boys.

A great singer didn’t need a computer to sound good. He or she needed a bottle of whiskey and some lyrics. The guitar player needed a producer to tell him, “Quit showing off.” Or, if the producer was really serious, “Sober up, and try it again tomorrow.”

Now bands go into the studio to wipe away all traces of the music they actually make.

Jesse Malin’s new album sounds exactly like Radio Disney. The keyboards. The guitars. The drums. All of it sounds like it was recorded for girls, ages six and under.

He probably thinks he’s being cutting edge.

I think I’m supposed to be talking about bootlegs. Townes has a bunch of those. His family has been reeling them in now, so they look like official releases, but the songs were usually recorded by a guy in the audience, and they’re all pretty good.

When Townes first started recording, back in the 60s, he recorded in studios, good ones, with a good producer, and the recordings are pretty fancy. His first album, For The Sake of the Song, takes a bunch of great songs and captures them in the worst possible way. Townes’ voice is dripping with reverb. There are enough strings to make a couple tracks sound Countrypolitan. The drums are so nervous and scattershot as to make the listener tweaky. The piano sounds wimpy. There are flutes. And harpsichords.

Someone somewhere must have imagined he could make some short-term money on Townes, so he did everything he could to cover up the fact that Townes couldn’t sing.

The producer, the record company, the money people, they must not have noticed that most of the great American singers can’t sing. Son House shouts. Bob Dylan does it with his breath. Hank Williams warbles. Etta James shouts. Townes Van Zandt belongs there, with the voices that people will find on their own and listen to forever. He didn’t need to be produced. He needed to be recorded. He needed someone with a microphone, and that was it.

My favorite Townes record is Live at the Old Quarter. It’s not a bootleg, but it’s of bootleg quality. It’s Townes and his guitar in a bar. The recording starts with Rex Bell, the owner of The Old Quarter, telling people where the restrooms, pool tables, and payphones are (upstairs). The cigarette machine is there, too.

After that, it’s all Townes.

He sings a couple dozen great songs in a voice that sounds a lot like the people who came out to see him, a voice that probably would have done a lot of good for the people who didn’t see him but would have recognized themselves in Townes’ songs.

If you’ve ever loved anyone or anything, you should buy Live at the Old Quarter. If you’ve ever gambled or worked in a bar or done too much cocaine, you should buy Live at the Old Quarter. Poets and truck drivers, peaceniks and nihilists, even lovers of Thunderbird wine should buy Live at the Old Quarter.

If you’re with me now, still, you should go and find some music that was made in a room filled with people and a couple microphones, music made by a guy who couldn’t sing but knew exactly what he wanted to say about the world.

Townes is singing as I write this.

Otherwise, I wouldn’t stop.

Dave Newman is the author of the novel Please Don't Shoot Anyone Tonight and four poetry chapbooks. He lives in Trafford, Pennsylvania.

|