SpottieOttieDopalicious Reflections On Cinema

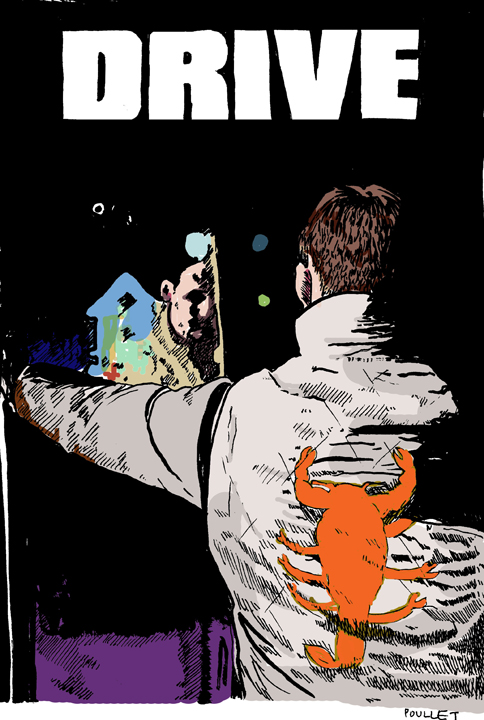

Drive: Sleek Noir & Progressive Pastiche

Jonathan Moody

Welcome to the promised land.

Locusts and all.

–James Sallis, Drive

Gorgeous cinematography. Los Angeles. A fatalistic, morally ambiguous protagonist who willingly decides to get sucked into a jacked up situation over a woman. These are typical film noir tropes that appear in Nicolas Winding Refn’s film Drive (2011); however, Irina (Carey Mulligan)—isn’t the femme fatale counterpart to Ryan Gosling‘s Driver. There’s no acerbic dialogue overwrought with innuendo, but the film’s retro-futuristic 80’s style soundtrack—packed with synths, Auto-Tune, & catchy lyrics of obsessive yearning—releases the sexual tension that Gosling and Mulligan suppress.

The film’s snail-like pace, which includes both sparse action and character development, is the antithesis of Sallis’ novella, which is action-packed and laden with background history. The major reason behind the film’s radical departure from the book is Refn’s vision of sleek noir; or, to use an ironic phrase that I’ve created, progressive pastiche. Refn, indeed, brazenly borrows both the gritty realism and the glossy images and surfaces characteristic of Michael Mann’s cinematic stylization in Heat. Although Refn isn’t concerned with the epic quest of exploring a protagonist’s or antagonist’s intricate character arcs, he and Mann showcase a similar aesthetic. Mann—in his stylistic endeavor to depict realism, to blur the line between movie-making and documentary through the use of grainy, digital camera footage—achieves his goal of providing an objective mirror of the actual world.

This world that Mann and Refn create is a nihilistic one (especially when it comes to matters of the heart). In Heat, Al Pacino plays an overzealous detective who has been through several marriages. There’s a haunting scene in which Pacino comes home from work and catches his current wife sitting in the kitchen with her lover. A great example of situational irony unfolds: the audience anticipates that the cuckold will draw his Glock and rough up the poor bastard and prove to his wife that he will no longer neglect her. But Pacino walks past him nonchalantly and says: “You can eat my food. You can sleep with my wife, but you can-not watch my goddamn TV!” While Mann uses humor to expand the rift between lovers, Refn relies on violence. Driver—who while zooming at maximum speed away from hired guns can maneuver his Chevy Impala 180 degrees on a two-lane highway & drive downhill backwards without veering his vehicle off the road—wrecks his chances of having a relationship with Irina; the brutality he unleashes on a henchman in an elevator to protect her backfires as she slowly walks away in disgust.

Refn’s film stays implanted in Los Angeles, whereas Sallis’ non-linear novella shifts back and forth between Phoenix and Los Angeles. In the movie’s stunning opening sequence, The Chromatics’ electro-pop track “Tick of the Clock” kicks the action into high gear as Driver meets his employer Shannon—played by Bryan Cranston from Breaking Bad—in a mechanic’s shop to pick up a silver Chevy Impala (an inconspicuous ride necessary for a getaway driver chauffeuring seedy criminals away from heists). Eluding squad cars in back alleys and police helicopters along a highway, Driver slows down and accelerates with ease. The nighttime aerial view of Los Angeles radiates with a cosmopolitan mystique that is the exact antithesis of the seedy underworld Driver inhabits:

Like most cities, LA became a different beast by night. Final washes of pink and orange lay low on the horizon now, breaking up, fading, as the sun let go its hold and the city’s lights…stepped in (Sallis 17).

The novella, however, begins with a suspenseful scene that appears in the film’s second act: the main character, Driver, stands in a second-floor Motel 6 unit and stares at a dead woman with half her face blown off, a pool of blood “moving toward him like an accusing finger” (2). There are two more dead bodies, males. One has succumbed to a Remington 870 shotgun blast, and the reader finds out later that Driver tossed a piece of broken bathroom window glass at the other henchman’s forehead like a dart. At the close of the first chapter, Sallis leaves his audience wondering how Driver ended up in Phoenix because the second chapter delves into the past, depicting Driver reading a crime novel in his LA apartment and suddenly stopping when he encounters the word desuetude. Driver walks to a nearby Denny’s to call one of his friends—a major Hollywood screenwriter—to inquire about the definition.

There are other figures in the book in which Driver establishes a rapport with clients and neighbors—even to the extent of divulging his tragic childhood. But Driver is more reticent in the film, However, judging by the lack of possessions in his apartment, it is clear that he’s very much the drifter that is described in Sallis’ novella:

Whatever he owned, either he could hoist it on his back and lug it along or he could walk away from it. Anonymity was the thing he loved most about the city, being a part of it and apart from it at the same time (18).

Even though he is reticent, Driver still ultimately becomes attached to Irina, a cute lady sporting a bobcat hairstyle, and her son, Benicio (her husband, Standard, is locked up but will soon be released on parole). Unlike the film, the novella doesn’t give the slightest notion of sexual tension between Driver & Irina; instead, Sallis focuses more on the budding friendship between Driver and Standard.

Despite the fact that critics blasted Drive for being derivative, the typical voiceover narration that offers slick, running commentary in most film noir has been removed like a candy-coated, customized paint job. In this sense, Refn adheres to the novella because Sallis’ book isn’t written from a first-person point of view. And the main character is not a gumshoe but a part-time professional stunt car driver who moonlights as a getaway driver—he is never the one pulling the heist, but he eventually attracts unwanted attention for coming into possession of heist money procured from a set-up disguised as a heist.

Most male noir protagonists who’re down on their luck encounter a mistreated woman who’s plotted a scheme to score cash. Although this man knows this female is unattainable and that this plan could cost him his life, he willingly participates in the scheme because he accepts that death is inevitable and that resistance is inappropriate. Irina doesn’t seduce Driver to bring about his descent. It’s the return of Irina’s husband—a flat character—that exacerbates everyone’s downward spiral towards tragedy. Driver, who witnesses the brutality unleashed on the husband for an unpaid debt, doesn’t think twice about offering his assistance—especially after he’s made aware that one of the goons who beat up Irina’s husband made Benicio, the son, hold onto a bullet as a souvenir. This moment marks a turning point where Driver’s alabaster veneer cracks.

Behind that tranquil demeanor, there lies a dormant beast raging inside; the orange scorpion on the back of Driver’s racecar jacket foreshadows the violence Driver will display after a botched heist between Irina’s husband and Blanche (who will end up with her face blown off in a hotel) that almost costs Driver his life. The racecar jacket, which has remained white, becomes stained. With blood. Blood. And more blood.

Critics have also found fault with the film’s “gratuitous” violence. One can assume that they haven’t read the novella that inspired the movie because the death totals in the book far outnumber the ones that occur in the film, and the manner in which the characters die is more gruesome. One can further assume that they are clueless regarding one of film noir’s most viable tenets: there’s no such thing as “gratuitous” violence because fate is one ruthless gangster who has a contract out on everyone’s head.

Jonathan Moody has become obsessed with David Grellier: the creative force behind the French electronica project called College whose 80's synths & neon album covers conjure a nostalgic craving for Knight Rider, V: The Mini-series, Mr. T's cereal, & purple & green glow light stick bracelets. Moody has three new persona poems in the voices of black comic-book superheroes Luke Cage, John Stewart (aka Green Lantern), & Steel forthcoming in Tidal Basin Review & currently has one published in Gemini Magazine. He lives in Fresno, TX.

|